Dice & Divinity

Playing with Religion in TTRPGs

PTFO:Stonetop’s hiatus continues, returning in late August. While Anwen, Padrig and Vahid trudge home after their defeat at Gordin’s Delve, I thought I’d continue to share some noodling I’ve been doing about fantasy, TTRPGs, and what I’ve learned from a few years of running the game solo. Today’s topic is religion and faith in fantasy fiction and TTRPGs. Hope you enjoy!

Faith in Stonetop

First, a bit of relevant biographics: I am not particularly religious myself. I was raised in a very secular household, and the circles I’ve moved in throughout my life are likewise secular. That being said, I’ve always been something of a religion enthusiast — Beginning when I was a kid going deep on Greek myths, I’ve spent a respectable amount of time digging into the cults, codes, and creeds1 of the faiths of the world, both living and bygone. In recent years, this curiosity has become a bit more practical: I’m raising two young boys, and as I attempt to impart a coherent and ethical worldview to them, I’m finding pure, modern materialism a little… thin.

Given all that, I didn't set out to write a lot about religion when I started PTFO:Stonetop, but I knew it was an exciting part of worldbuilding for me. The game’s setting has some loosely defined gods and religious traditions that the GM is supposed to make their own, and I intended to do just that: Build out the Stonetop faiths to add some Iron Age window dressing to the adventurous proceedings.

As I played through and envisioned the PCs, the supporting characters around them, and the hopes and fears that motivated them, I found faith cropping up again and again. There have been many moments where religion and faith play a key role in the story — we’ll get into a few examples below. I’ve found this element of PTFO:Stonetop to be one of the most creatively rewarding parts of the project, bringing a lot of richness and texture to the world and characters as I’ve played through it with y’all.

Fantasy’s Mala Fides

At the same time I’ve been writing Stonetop, I’ve been doing my best to read great fantasy as well (though I have the same reading malaise that seems to have a lot of folks in its grip), and it’s tough out there for organized religion. My latest read is Joe Abercrombie’s The Devils, a grim, bloody romp through an alternate-fantasy Europe with flesh-eating elves invading from the Eurasian Steppe, a religious schism between the Holy City in the West and the Eastern Empire of Troy, and other dark, delightful history-twisting worldbuilding.

I like his work. I count The First Law trilogy, the Shattered Sea trilogy, and The Heroes among my personal faves. But when it comes to the subject of faith, he can be a bit one-note:

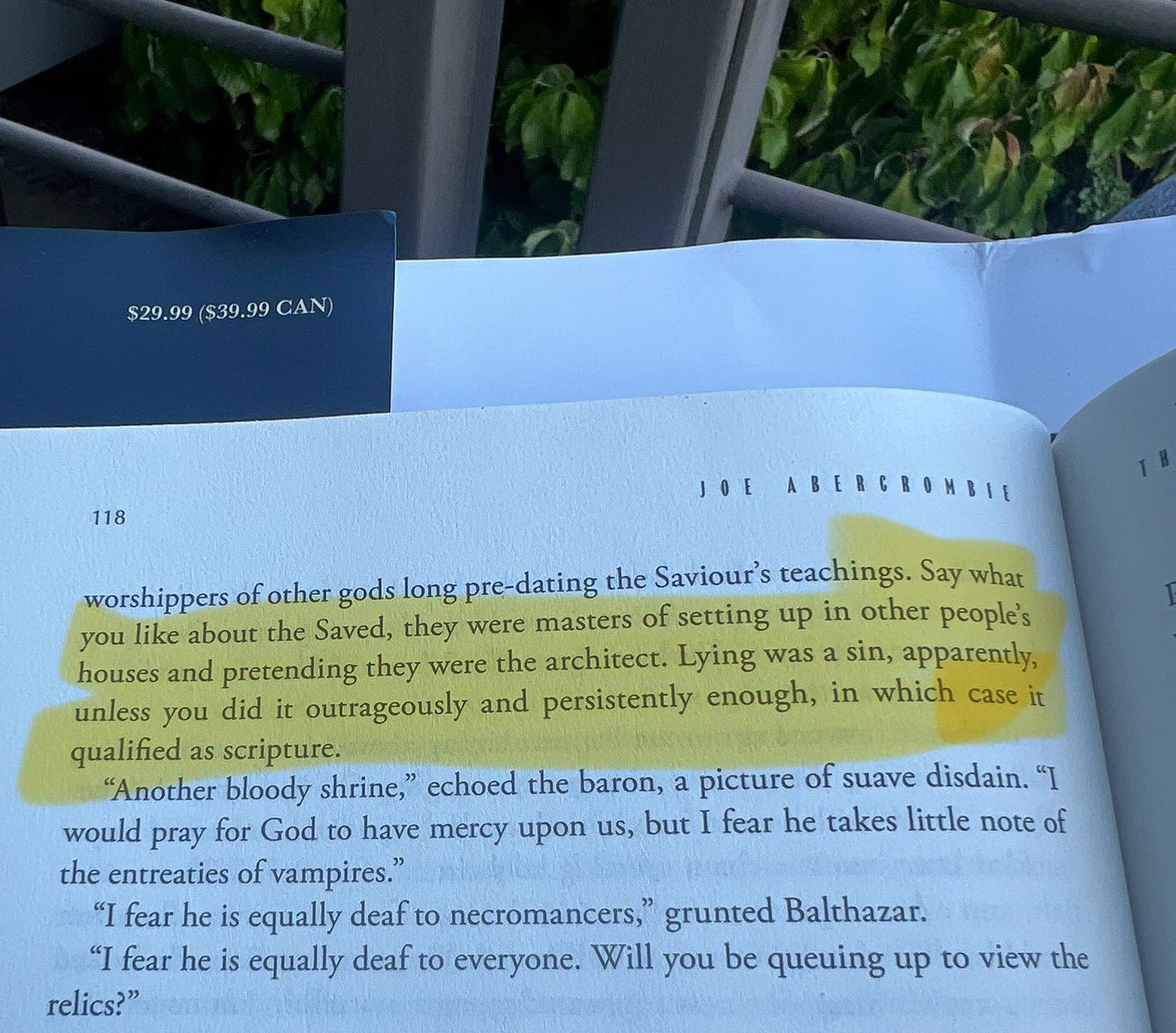

It’s all like this. Faith and religion are a grift, perpetrated by devious liars on credulous, unfortunate fools. His whole body of work holds this perspective; it seems to be a fixture of his vision of dark fantasy. I haven’t finished The Devils yet, so it’s possible that in the end, the church of the Saved reveals itself to have some redemptive character, but that has not been the case in Abercrombie’s other work.

When I look at the rest of my recently read and to-be-read pile, the rest is not much different. I’ve been marching through the Horus Heresy novels, and the universe of Warhammer 40k is not, I regret to inform you, filled with god’s love. I recently read The Will of the Many, which has a Roman-inspired pantheon and a church that ostensibly represents that faith, but these gods are not represented as present in the world, and are quite separate from the Will-magic/tech at the heart of the story’s premise. A faith that inspires and uplifts would bump up hard against the book’s themes of hierarchy and exploitation.

I’m sure there are counterexamples that I haven’t read — if you have any, feel free to post ‘em in the comments. But any counterexample aside, there does seem to be a strong irreligious current in fantasy fiction — the genre has come a long way from C.S. Lewis’ religious allegory and Tolkien’s religious non-allegory. If this is indeed a trend, or at least a current in the genre, why should we care? What’s lost when fantasy becomes disenchanted?

Getting Stuck in Poughkeepsie

I like a lot of these books, but they do seem to be missing something from the fantasy genre. Ursula Le Guin, one of the early luminaries of the fantasy genre, wrote an essay in 1973 called “From Elfland to Poughkeepsie” — Elfland being the term she chose to represent the ‘second worlds’ of the fantasy genre, like Middle-Earth, Cosmere, or Azeroth:

“Let us consider Elfland as a great national park, a vast and beautiful place where a person goes alone on foot, to get in touch with reality in a special, private, profound fashion. But what happens when it is considered merely as a place to 'get away to"?

…

A great many people want to go there, without knowing what it is they're really looking for, driven by a vague hunger for something real. With the intention or under the pretense of obliging them, certain writers of fantasy are building six-lane highways and trailer parks with drive-in movies, so that the tourists can feel at home just as if they were back in Poughkeepsie.”

But the point about Elfland is that you are not at home there. It's not Poughkeepsie. It's different.

In this essay, Le Guin was concerned with prose style — in the 70s, there was a proliferation of fantasy writing that was written in modern language English, a significant departure from the elevated, mythic prose of writers like J.R.R. Tolkein and other contemporaries like E.R. Eddison and Kenneth Morris. For Le Guin, fantasy written in modern language lost its transportive power, its ability to take you from Poughkeepsie to Elfland.

Well, one of the ways that I always feel like I’m in Poughkeepsie and not Elfland when I’m reading a fantasy story or playing a fantasy game is the persistent sense that the thoughts, values and beliefs of the characters are those of the modern moment, with a thin lacquer of fantastical worldbuilding.

Re-enchanting the Gaming Table

If you’ve read this far, you’re probably a creator of fantasy fiction yourself — maybe you’re a writer, maybe you play in a solo RPG or at the table with friends. Maybe you’ve felt a pull to make your fantasy world a little more fantastical, maybe you’re looking for ways to more fully envision your characters and the worlds they inhabit. If so, here are three approaches I’ve found to incorporate religon, mysticism and faith into the PTFO:Stonetop campaign that have helped me escape Poughkeepsie.

Cult: Prayers and Rituals

Whether one is religious or not, it’s possible to see beauty in words of prayer, and words of prayer are among the most memorable parts of beloved fantasy and sci-fi stories.

Litany Against Fear

"I must not fear.

Fear is the mind-killer.

Fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration.

I will face my fear.

I will permit it to pass over me and through me.

And when it has gone past, I will turn the inner eye to see its path.

Where the fear has gone there will be nothing. Only I will remain."

Quite the banger. ‘Litany’ is just ecclesiastic Latin for ‘prayer,’ so this example, from the first chapter of Dune, certainly qualifies as religious content. Dune is shot through with religion: Frank Herbert envisioned far-future faiths like Mahayana Christianity and Buddislam, all fused into a single religious text, the Orange Catholic Bible. This Imperial faith is contrasted with the Fremen’s faith (which we learn was shaped by the meddling of the Bene Gesserit). But most people do not remember those elements of Dune’s world — they remember the prayer.

I’ve indulged in the opportunity to write a number of original prayers in PTFO:Stonetop. The first one was back in Session 9.4, when Anwen and Padrig accompanied the hunters’ lodge on a hunt to bring down a massive cave bear:

“This is the place.” Hywel growls. “Come here, girl. Let us speak to god together.”

The other hunters busy themselves with preparations, gathering deadfall branches and piling snow for hunter’s hides at Pad’s direction. Anwen stands before Hywel, and takes from his pack a palm-sized stone pot, sealed with wood and wax. He cracks it open, and Anwen smells the metallic tang of blood.

“Hare’s blood. Stag’s would be better, but we have none. Kneel, girl.”

She kneels before Hywel, and he paints her cheeks and forehead with red. For a moment, Anwen thinks of Kirs’ face, painted with his horse’s blood to draw the carrion drakes near, and she suppresses a shiver.

“Tor, Slayer-of-Beasts, hear me, for my people are hungry,” Hywel whispers, his bloody hand on Anwen’s forehead. “We dedicate this hunt to you. Lend your daughter the swiftness of the hare, to slip the jaws that snap and claws that catch. Let our quarry think us rabbits, when we await him as wolves. Let us be the hunters this day, and not the prey.”

This was a lot of fun to write, and I was pretty chuffed with it. It’s no Litany Against Fear, of course, but it did the job Hywel and Anwen needed it to do. I valued the opportunity to get into Hywel’s head enough to envision how he might talk to god. Stonetop’s world is filled with dangerous megafauna, not just lions, tigers, and bears, oh my, but Smiledons, mammoths, thunder drakes, and Frythanc, too. Naturally, his prayer would acknowledge that humans are not always at the top of the food chain.

Writing a prayer for your characters or NPCs in your game is a fundamentally similar project as writing a poem, a song, or a legend — it requires you to dig into the fears, hopes, and values of the person who recites it. Doing it creates a sense that the world you’re envisioning is ancient and lived in, and not merely the soundstage for some swashbuckling adventures.

Writing one from scratch is tricky, of course, and you certainly don’t have to. There are millennia of prayers out there waiting to inspire you. In Session 8.4, I cribbed from Ecclesiastes 9 for Solnn’s funeral prayer:

“Heol, bringer of light, we bring you our dead. Their love and boldness, their weakness and envy have now perished, and nevermore will they have a share in any deed done under the sun.”

The procession mutters in unison, “Heol kemn.”

Solnn turns and addresses the mourners. “With Heol’s setting, they depart from our band, the Crowmother bearing them to the shining throne. If they could speak, they would bid us this: Go, eat your food with gladness, and drink with a joyful heart, for Heol shines his light upon you for another day. Be clothed in white, and mark your skin with ink. Enjoy this life with your mate, whom you love, each of the days of this vain life that Heol dawns upon. Whatever your hand finds, be it bow or crook, loom or needle, a child’s cradle or a shining blade of bronze, toil with all your might, for at the foot of Heol’s throne, all are made equal, and in the golden realm of the dead there is neither toil nor glory nor knowledge nor wisdom nor suffering.”

And here’s the meat of the original, from the NIV translation:

Go, eat your food with gladness, and drink your wine with a joyful heart, for God has already approved what you do. 8 Always be clothed in white, and always anoint your head with oil. 9 Enjoy life with your wife, whom you love, all the days of this meaningless life that God has given you under the sun—all your meaningless days. For this is your lot in life and in your toilsome labor under the sun. 10 Whatever your hand finds to do, do it with all your might, for in the realm of the dead, where you are going, there is neither working nor planning nor knowledge nor wisdom.

Adapting this was a fun little creative project — a bit hacky, maybe, but still satisfying in all the same ways it was when I was writing the huntsman’s prayer for Hywel.

Code: Characters and their Values

Stories — particularly TTRPG stories — are made of obstacles. Almost every scene has at its heart a character wanting or needing something, and not being able to get it because of some barrier. Often, those barriers are other people — nefarious villains, arrogant princes, officious governors, and the like — and even in Dungeons & Dragons, you can’t just stab all of them, right? Sometimes, you have to persuade them.

And how do you do that? You can always appeal to their self-interest. But in a world where the gods are real and a religious code is part of how people define themselves, there are higher ideals to appeal to.

When Frodo suggested that it would’ve been better if Bilbo had killed Gollum after taking the ring from him, Gandalf delivers the following classic line:

“Many that live deserve death. And some that die deserve life. Can you give it to them? Then do not be too eager to deal out death in judgement. For even the very wise cannot see all ends. I have not much hope that Gollum can be cured before he dies, but there is a chance of it. And he is bound up with the fate of the Ring. My heart tells me that he has some part to play yet, for good or ill, before the end; and when that comes, the pity of Bilbo may rule the fate of many - yours not least.”

Middle-Earth doesn’t have organized religions, but it does have deeply held virtues like courage, mercy, and hope, and here Gandalf makes the case for them. He could’ve said “Well Frodo, you’re going to have to go to Mordor and that weird little gremlin is the only one who can get you there unseen, so suck it up.” Instead, he appeals to the angels of Frodo’s better nature. He is persuaded, and it is through his forbearance of Gollum that the One Ring is ultimately destroyed.

To execute on this at the TTRPG table, you need characters who are strongly motivated by their creed. In Stonetop, one such character was Abrim, the Chained Judge of Gordin’s Delve. Once a firebrand priest of Aratis the Lawgiver, he attempted to bring law and justice to Gordin’s Delve and led an ill-fated uprising against the Delve Bosses. When the PCs met him, he was held prisoner by Jahalim of the Keys, forced to use his sacred authority to mediate disputes in his jailer’s favor.

When the PCs were trying to muster Gordin’s Delve to defend against the sorcerer’s coming attack, they needed to unite the people under the Bosses, who had not been gentle rulers in the past. They needed Abrim’s moral authority — the blessing of Aratis might convince the people of the Delve to risk their lives in a desperate defense. Vahid could’ve made the practical case: Do this, or the sorcerer’s armies will simply kill you, along with everyone else in the Delve. But instead, Vahid appealed to his Faith:

Jahalim gestures for Abrim to join them at the table. After a long, reluctant pause, the Judge clanks forward, dragging his fetters behind him. “What of it, Abrim? If we release you, will you intercede on our behalf to the people of the Delve? Place Aratis’ blessing on us as their leaders after all that has passed between us?”

Abrim doesn’t look at him — he holds his gaze on Vahid. “You ask much of me, Seeker. And of my god. To place Aratis’ sacred mantle of rulership upon these villains is an abomination.”

“Not so. I have studied the Heiros Nomos, as I know you have, and the histories of Salonius and Hierotytos besides. After the Sorcerer-Kings fell, the first great chieftains to replace them were mere brigands and highwaymen. Until Aratis’ true disciples raised them up and taught them justice.”

Abrim regards the Bosses, hope and contempt at war on his face. “This is crooked timber you offer me to build a temple to my god.”

“Have you not considered, my friend, that this is the task for which she preserved you?” Vahid asks.

Abrim was persuaded and lent his aid in the defense of the town. Unfortunately, they were defeated, and the town was burned, but we have not seen Abrim dead — he still may be alive, still building that temple to his god. I had a lot of fun writing this exchange, and it added a really different flavor to the proceedings, which ran the risk of being one-note if it was just Vahid browbeating a bunch of petty ganglords.

Creed: Worldbuilding & Factions

In a fantasy story, especially a story in a TTRPG, it is expedient to have bad guys who do bad things, and must be stopped. Orcs and goblins are a classic — they burn farms and slaughter livestock, and carry good folk off to be enslaved or cooked in stewpots. Killing them and looting their mangled corpses is practically a moral imperative.

But it’s OK to want something with a bit more nuance than that. “Evil Orcs” are a topic of frequent TTRPG discourse on Twitter and elsewhere, but even if you’re fine with epistemically evil monsters, it can start to feel a little flat. Even if you’re telling a straight good-versus-evil story, it’s better craft if your villains have a credible argument as to why they’re the good guys, actually.

The MCU’s version of Thanos is a solid example from recent mythmaking. In the original Infinity War comics saga, Thanos’ true agenda was to win the love of Death, and the universe’s sustainability problems were not his primary concern. In the films, the idea of ‘balance’ is put center stage so Thanos can proceed with a somewhat coherent worldview that demands he exterminate half of all life on earth.

In PTFO:Stonetop, the main antagonist, Cirl-of-the-Storms, has a worldview profoundly shaped by his faith — specifically, the worship of Tor. In PTFO’s version of the Stonetop world, the Hillfolk nomads are divided into two sects — the Heolings, who worship the sun god Helior, whom them name Heol, and the storm-folk, who worship the thunder god Tor (also worshipped by the village of Stonetop). In our ancient history of these peoples, the Hillfolk were enslaved by the Makers, and it was the storm-folk who finally overthrew them (in part through the use of dark, corrupting magics). Those storm-folk then rose to become the Sorcerer Kings, using the power of the Makers and the dark magic of the Things Below to become powerful and wealthy. They were subsequently overthrown by their Heoling brethren and have been in decline ever since.

In Vahid’s vision under the Fate-Tree in Session 7.6, we saw a young Cirl with his aging mentor, who laid out their version of history:

“Once, when our people were kings, the tu’d was like a great spirit of the storm — we rode where the wind took us, falling upon our enemies like a thunderbolt. The Despots of Lygos, the Jarls of the Manmarches, the captains of the mountain holds — they paid us a golden treasure to turn our wrath away from them. Once I thought I would live to see those days come again, but it feels like a distant dream now.”

“Dreams can be made real, if the faithful fight for them,” Cirl replies. “You told me that.”

The old man nods, his face growing wearier. “I will fight. But you must live to fight another day, boy. Work your magic — bid the wind to hide you, and do not make a sound. If they take me, perhaps they will be satisfied.”

In the rest of the scene, we see how the Heoling witch-hunters persecute Cirl and his master, leading to Cirl becoming a hdour and turning to darkness. Cirl wishes to see his old master’s dream realized, the storm-folk ascendant again. This historical grievance doesn’t make his actions in the present any less evil, but understanding this deeply held motivation makes the world feel more alive and gives us a sense of why he is able to attract an army of fanatics to his banner.

Finding the Path Back to Elfland

As I said at the outset, I’m not a particularly religious person. But I do love to play pretend, and to imagine worlds different from our own. There are lots of ways to do that at the gaming table, but faith and religion are a less-taken path into Elfland. Modern life can feel very disenchanted, and envisioning a world where the divine is present and deeply felt can be powerfully transportative, even for the resolutely secular.

What’s been your experience with faith at the gaming table and in fantasy fiction? Do you incorporate religion or faith into your TTRPGs, either as a player or GM? If you've been following PTFO:Stonetop, did you notice the religious elements we've been discussing, or were they more in the background for you?

These are the three pillars of a faith: Creed, the doctrinal beliefs and assertions about the nature of god, spirit, and the divine; Code, the rules of ethical and moral conduct; and Cult, the ritual and worship practices. This framework seems ubiquitous, but doesn’t seem to have a clear origin point.

I hear 'Elfland' and go straight to Lord Dunsany' 1924 'The King of Elfland's Daughter.' That and the prog folk / rock album that was inspired by it (Mary Hopkin, Christopher Lee etc...). I'm sure Ursula was paying homage to the novel.

A few years back, I was playing a long term PBP and my character at the time, an Elf Wizard, was trapped in the armoury of a load of angry blood-sacrificing Dwarves.

The elf was, somewhat screwed, at one being subjected to a salvo of 12-ish javelin attacks per round. Lightning was flung, deflector shields were being burned through at a rate of knots and he was stabbing away with his shortsword at those beating on him in mélée.

Riffing heavily off Mr Herbert's Litany and others from um... the bible, I hastily cobbled together this piece of dogrel, as the Elf Wizard commended his soul to his diety and made peace with going down fighting. (I later retconned it as a pre-existing Elvish battle prayer.)

Litany of Lucky Arrows.

Let our lucky arrows fly from afar,

Let our silver blades be bright,

Let our woven spells be sung in the night,

Let our wit's barbs be sharp,

Let our souls fight with you,

Viethiel Vandrian!

Let our lucky arrows fly true,

In Your Name.

Elf survived, dice were lucky, companions eventually came back after running off. Later, the character was heralded as an avatar of his god.

So yeah, love a bit of mysticism.

I love Abacrombie. My take on his depiction of religion is that he's more interested in human fallibility both within organised religion, or power structures in general, rather than any dismissal of spiritual practice. I feel like a lot of that comes from him choosing to show the world through dramatic character experience more than descriptive world building. That said, I've really enjoyed the religious details you've added in PTFO: Stonetop. It absolutely deepens the world, giving it texture. So, maybe Joe could learn a thing or two ;)

In terms of ttrpg play, my current campaign revolves around a world in which religion has been forgotten and the gods left weak without worship. In a last ditch effort, the gods have chosen a handful of heros to spread hope and faith, to unite and defend against an unfathomable evil which has begun its play for the surface world in the god's absence. Nothing special of note in the setup but, what has repeatedly surprised me is my players suspicion of the very gods that grant them their powers, and their reluctance to formalise any form of religion, even when it is demonstrably beneficial for themselves and the populace.