Session 4.2: A reasonable man

Vahid demonstrates his power. Anwen seeks the truth. Padrig confronts Brennan.

In our last episode, the party arrived in Marshedge. While Vahid and Ozbeg secured lodgings, Anwen was the victim of a pickpocket. She and Padrig pursued the thief into Lowtown, where they encountered another of Padrig’s old bandit comrades, a hulking brute named Ivan. During the confrontation, Anwen was hurt quite badly and had to return to the inn to recuperate. Meanwhile, Padrig and Vahid went about their businesses — Vahid to meet with a powerful merchant and Padrig to meet with his old chief, Brennan.

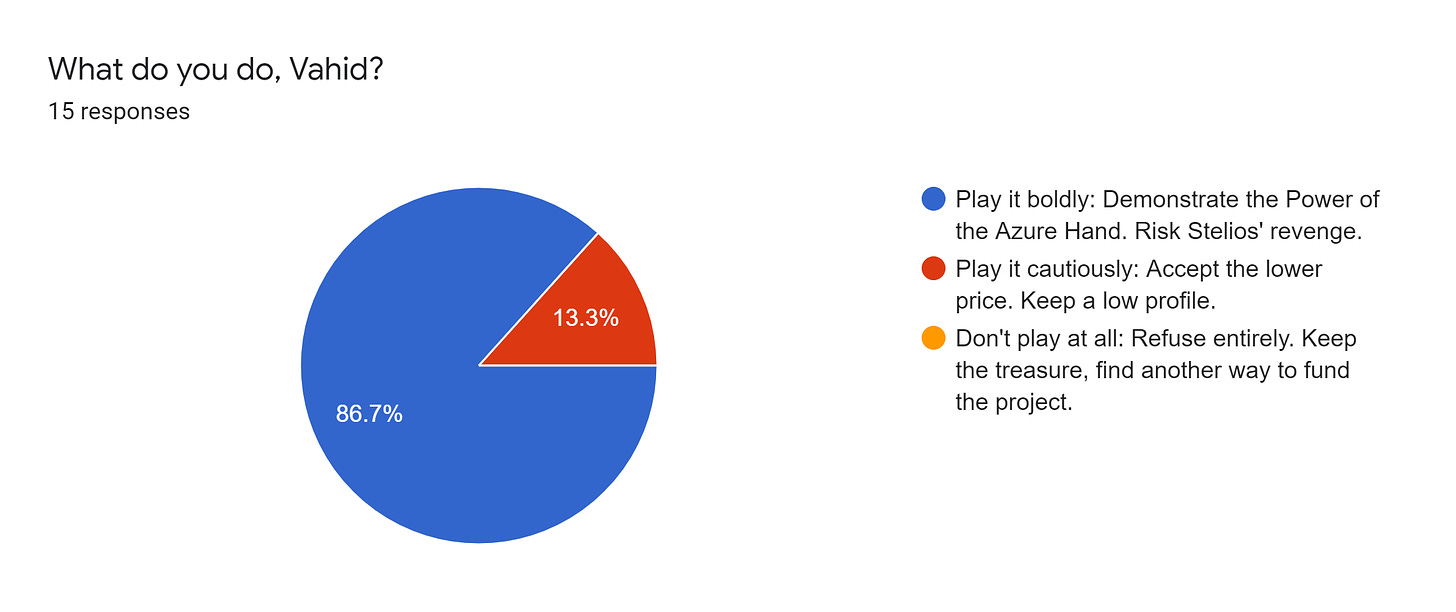

We ended last episode with the merchant Tymon Ammar requesting that Vahid demonstrate the power of the Azure Hand. If he does so, he will get the coin he requires (and win Tymon’s friendship), but will expose himself to danger from rivals in Lygos. We put the choice to the readers, let’s see what you folks chose:

Quite a one-sided vote, this time. I was of two minds about this reader poll: On the one hand, it’s absolutely a choice a GM would offer a player at the table for a Weak Hit — it introduces a cost or consequence to the goal the player was pursuing. But in terms of keeping things exciting, it’s probably better that Vahid takes the risk. I’m curious if you all think these kind of game-y decision points are worthwhile to include, or if we should really only focus on more pivotal, ambiguous character decisions. If you feel strongly one way or another, let me know in the comments. I am going to try to incorporate this sort of interactivity as frequently as possible, but I want to make sure they’re choices that you folks are interested in making.

So, Vahid will be bold, and demonstrate the power of the Azure Hand. All that remains to be seen is whether he can control it.

Seven, plus Vahid’s +1 CON, make for an 8 — a weak hit. It takes all of his focus, but he successfully invokes the artifact.

Scene 2, Continued: A Stone Manorhouse

Vahid ponders Tymon Ammar’s offer, tapping his finger sharply on the wooden table. Tymon waits patiently with a faint smile. “One hundred gold bezants,”1 Vahid says finally. “The works of the Makers are of great worth, but the truth is priceless, is it not?”

The smile fades from Tymon’s face. “You presume too much, ebn Sulaim.”

“If you can find another who can offer you what you ask for, Master Tymon, I will match their price,” Vahid replies.

Tymon laughs sourly and produces a heavy pouch of purple silk. “Such cleverness. No doubt you were every teacher’s favorite.”

“At first, yes,” Vahid says, rising from his seat. “But not for long.”

Vahid feels the thrum of the Azure Hand even before he opens its case and takes it up. With the staff in hand, Vahid can sense the heat from the coals, bleeding into the cool, damp air of the great hall. As the Hand’s perception extends outward, Vahid can feel the presence of the Makerglass in the chandelier above — each one smoldering with a heatless fire, bound in the crystal shards. Vahid idly wonders what power those shards might have contained when whole, before putting his mind to the task at hand.

Eyes closed, brow knit with concentration, Vahid strikes the stone floor with the staff, and as the sound reverberates throughout the hall, the red coals in the hearth begin to pop and hiss, their glow first turning to yellow, and then burning white-hot. Flames come to life, first a flicker and then a roar, streaking unnaturally through the empty air towards the staff’s aetherium head to encircle it in a fiery ring.

Tymon stares in open-mouthed admiration, the swirling firelight reflecting in his optics. “Incredible,” he breathes.

Vahid cannot answer — all his focus is on the Azure Hand and its tenuous grip on the elemental power that surrounds it. Before it can escape, he holds the staff aloft and casts his unseen hand towards the Makerglass chandelier overhead, pouring the energy into the shards. As the crystals drink in the flames, their glow swiftly intensifies and clarifies until the room is suffused with a pure, unrelenting white light.2

It takes a few moments for Vahid’s vision to clear, and even then, the afterimages of the twelve points of light persist. A slow, echoing tapping echos through the hall, and both Vahid and Tymon turn to its source.

It is a thin and crooked old man, bald but for a salt-and-pepper beard. He is leaning on a lacquered ebony cane, topped with a heron roughly carved in white soapstone, which he is tapping on the stone floor, an expression of curiosity on his deeply-lined face. The servant who admitted Vahid stands attentively at his elbow.

Master Tymon rises to greet the newcomer. “Master Hawtrey, I hope our business did not disturb you. I had requested a certain demonstration, and my guest obliged me,” he says.

Grandfather Hawtrey shakes his head dismissively and totters towards them. “The reason you are welcomed into my home, Master Tymon, is because you gather such interesting folk to you,” he says with a raspy chuckle. “Who is this man?”

Tymon introduces Vahid with a flourishing gesture. “Master Hawtrey, allow me to make known to you Vahid ebn Sulaim, a scholar of the Lycaeum and student of the great works of the ancients,” he says.

Vahid bows respectfully. “A great pleasure, sir, to make your acquaintance and to be so welcome in your household,” he says.

“Master Tymon is welcome, sir. You, I do not know yet. I see you have learned some of the Makers’ tricks. What manner of sorcerer are you? A teller of fortunes? A spitter of curses? A weaver of illusions?” he pauses. “A healer of the sick, perhaps?” he asks suggestively.

“I am afraid not. Sorcerers are fools who command power beyond their understanding. It is understanding that I seek, first and foremost. I am no sorcerer — as Master Tymon said, I am but a scholar and a student,” Vahid replies.

“A shame,” Hawtrey says. “Sickness has cast a shadow upon my house. My only son, Lugh, has fallen into a deep slumber and cannot be roused, though he still breathes and takes food and water. Every Master of the herbalists guild has tried their vile concoctions upon him, to no avail. They only make excuses and claim it is no natural sickness. If in your studies of the unnatural, you come across something that might help him, it would be worth your weight in gold to me. Whether or not you understand it,” he concludes with a pointed look.

Vahid bows his head in sympathy. “If I find such a thing, Master Hawtrey, you will hear of it.”

Hawtrey, momentarily overtaken by emotion, clears his throat and now turns to Master Tymon, and business. “I hope your journey here was less troublesome than your last, Tymon.”

Tymon smiles. “It was indeed. My guard captain hired on extra swords for the trip after our bandit trouble in the Manmarch last summer, but we were not bothered at all,” he says.

Hawtrey grins smugly. “Yes, I hit upon a most excellent scheme — one of the bandits, a fellow named Brennan, is quite a reasonable man and has come over to our side. In just a few months, he’s taken the matter of the other brigands well in hand — hanged a dozen of them from the gatehouse last month. It made an impression.”

“I’m sure it did,” Tymon replies. “But can he be trusted?”

Hawtrey waves his cane dismissively. “He, like many, is motivated by gold. I have that in abundance. I’ll keep him on a short leash, never fear. And now that the roads are safer, it seems a good time to discuss your spice contract. I seem to recall you chiseling me for a few hundred bezants last year over your bandit woes.”

Tymon grimaces, but before he can reply, Vahid cooly inserts himself. “Honored elders, I think it is time I take my leave. Master Tymon, is our business concluded?”

“It is, ebn Sulaim,” Tymon says, smiling with anticipation. “When I return to Lygos this summer, I will bear glad tidings to our friend Master Stelios.”

He hands the silken purse to Vahid, who is startled by the weight, nearly letting it drop to the ground. Tymon chuckles. “Unaccustomed to the feel of gold? That will soon change, now that you and I are friends.”

We’ll close Vahid’s scene here — he’s secured the funds, he’s made a new friend in Tymon Ammar, and a new enemy in Master Stelios. He’s also learned about an opportunity — Grandfather Hawtrey’s son and heir, Lugh, has been laid low with some sort of mystical illness and can’t be cured.

We also fleshed out Brennan’s position in Marshedge a bit, seeing another angle of his rise to power here. As the conflict with Brennan comes more into focus, Hawtrey might become an important side character — we’ll have to play to find out.

The rest of Vahid’s activity in Marshedge (i.e., purchasing the building materials he’s here for), we can abstract — he’s got the coin, and they’ve already made the arrangement with Kiran, the trader from Episode 2.2. Vahid managed to squeeze Value 4 out of Tymon Ammar, so he can pay for the Value 3 trade goods and still have a healthy sum left over to take back to Stonetop.

Next, we’ll spend a bit of time with Anwen, before closing the episode out with Padrig. She is recovering from her injury in her confrontation with Ivan — last session she ended with just 6 HP remaining, after a rest at the inn she’ll be back up to 14 HP. This rest was also unusually comfortable — they’ve spent 8 days sleeping on the hard stone of the Makers’ Roads, and a straw mattress in Marshedge feels like the height of luxury, so the Make Camp states she’ll get advantage on her next roll.

That next roll is Ask Around, the same move Vahid used to locate Tymon Ammar. Here’s the move text:

Anwen hopes to learn about her mother, who returned to Marshedge four years ago. Anwen has her mother’s name and description, and she knows that her husband (Anwen’s father) was a hero hunted monsters in the Fen. That said, she’s cautious about revealing too much — the confrontation with the Judge at the Crossroads in Session 3.2 left her uncertain about how truthful her mother was being all this time. Rolling with advantage, she scores an 8, so she has to choose a complication. Anwen doesn’t have a extra purse of coppers, and the party probably has enough unwanted attention from folks like Ivan and Bertrim, so she’ll choose unclear information with an opportunity to learn more.

Scene 3: The Tricklebank Inn

Anwen awakes in their room in the Tricklebank Inn to the sound of a rhythmic scratching. As her eyes adjust to the candlelight, she sees Ozbeg, seated on his straw-stuffed mattress, sharpening one of his fighting knives on a leather strap. “Where are the others?” she asks.

Ozbeg doesn’t look up from his task. “Gone to the hilltop. Vahid to see some fancy merchant, Padrig to see the chief.” He scrapes the blade across the leather again before testing the edge against his thumb.

“Are you worried?” Anwen asks, sitting up on the mattress and pulling her boots back on.

“What’s to be worried about? Padrig’s stuck by Brennan for a long time. Longer than anyone could’ve rightly asked for. If he says he’s done, the chief has to listen to reason,” he says. “He’s a reasonable man, ain’t he?” Ozbeg sheathes the knife with a snap.

Anwen stands. Her face is still tender to the touch where Ivan struck her, but the pounding in her head has subsided. She drapes her mother’s grey cloak around her shoulders and heads to the door. “Where are you off to, girl?” Ozbeg grumbles. “Best we wait for Padrig to return.”

“I won’t find my mother sitting in our room, Oz. I’m going to see if I can find someone who knows her, starting with the publican here,” she says.

“Well, you ain’t going alone. If you go missing in an alley somewhere, I’ll never hear the end of it,” Ozbeg replies, rising and collecting his gear to follow her.

Downstairs in the common room, the mood is quieter — the caravan guards and traders have retired for the evening, and the innkeeper is making a slow circuit of the floor, collecting empty wine jugs and resin-caked clay pipes, while a few remaining patrons murmur at the corner tables. Anwen approaches him and he turns to her with a tired smile. “Yes, lass? We’ve doused the cookfires for the night, but there might be some victuals left if you’re hungry.”

“I wanted to ask you if you knew of a certain woman who came to Marshedge four years ago. She might have come through your inn. Her name is Sianna, she has red hair — like mine — and has seen 37 winters,” Anwen says.

The innkeeper shrugs apologetically. “Sianna is a common name here — named for Sianna Ferrier, who founded the town and taught our people the ways of the Fen,” he says, making a respectful gesture at the mention of her name. “What was her trade? Might be one of the guilds has a record of her.”

Anwen is taken aback. “I’m not sure. In Stonetop, she was herb-wise and fletched arrows for the hunters,” she says. “She was married to a man named Connor. He hunted the monsters of Ferrier’s Fen to protect the people here.”

The innkeeper’s brows rise quizzically. “You don’t know much about Marshedge, do you, girl? The only folk around here who hunt the monsters of the fen are the fen-walkers. Their guild master goes into Lowtown and the Mires every four years and recruits from the dregs — orphans and the like — and trains them as best they can to survive in the fen and keep its monsters at bay.” He turns up a stone mug and fills it with a dark brown beer, offering it to Anwen before continuing. “Most don’t survive long — the fen isn’t kind to them. Even if they stay ahead of the jaws and claws, sickness takes many of them. If they’re lucky, it kills them. If they aren’t, it changes them to something that isn’t human anymore. They aren’t allowed to marry or to sire or bear children, on pain of death, for all concerned. Can’t be sure that the sickness won’t pass on, you see.”

Anwen sips the beer, quietly nodding. The innkeeper leans in. “So, if you were looking for Sianna, who’s ‘married’ to Connor, the fen-walker, you might ask at the fen-walker’s guildhall. And you might be careful what you say,” he says.

“And what will you say, innkeep?” Ozbeg grumbles.

The innkeeper shrugs. “Don’t see that it’s any of my business. Best to keep out of my customer’s comings and goings. So long as the tab is paid,” he says, looking down at the barely drunk beer.

Ozbeg throws a few silvers onto the table. “For your service,” Anwen says, as the two decamp from the inn and onto the streets of Edgemarket, in search of the fen-walker’s guildhall.

NPC Breakdown: Ludig

Next, we’ll rejoin Padrig. So far in Marshedge, we’ve introduced two significant ex-bandit NPCs — Bertrim, a sly, smarmy operator, and Ivan, the brutal champion of the Claws. We’ll want to introduce one more before we meet with Brennan — someone that represents the part of Padrig’s former bandit crew that might be worth saving. If all the ex-Claws in Marshedge are irredeemable bastards, that might make things a little too easy for Padrig, and we don’t want that.

Heading over to the Ironsworn Character Oracles, we’ll grab a character role, and descriptor: Healer, Influential. Ludig, a Manmarcher, is the crew’s surgeon, and well-liked by the other Claws — likely because he’s saved more than a few of them from death or disease.

Scene 4: Outside the donjon

The donjon of Marshedge sits astride the stone wall that encircles the hilltop and keeps the manor houses of the Old Families and their most valued retainers separated from those of the common folk below. The founders built the wall, but the donjon itself is much older: a ruined stone tower, created by the ancients from massive granite slabs, arising out of the hillside from a foundation sunk deep into the earth. The tower’s collapse begins two stories up, and the ever-practical founders of Marshedge augmented the structure with timber towers and walkways that command a view of both the fen to the north and the town’s fields and rice paddies to the south. Padrig approaches the looming structure with a pit of doubt in his chest, which he pushes down as he reaches the stairway up to the holdfast.

The stone steps leading up to the donjon’s gate are steep, made for the ancients and not their human servants; each comes up to Padrig’s knee. Fortunately, a narrow wooden stairway has been built atop the original stone stairs, providing an easier climb. When Padrig reaches the top, he makes note of the defenses — on the landing is a barrel that reeks of pitch, and commanding a view of the stairway is a guard’s walk with slitted timber shields. A few guardsmen take note of him from above, pointing at him and talking among themselves.

As he approaches the main gate, Padrig spots an old friend. Ludig is a thin Manmarcher with blonde-white hair and red, sun-scarred skin. He wears simple grey wools and a well-worn butcher’s apron, freshly cleaned but stained with old blood. When he sees Padrig, first his jaw drops, and then he runs forward to take his arm in greeting. “Tor’s bloody guts, Padrig. You made it. We all thought you were dead,” he says.

“I’ve heard that a few times today,” Padrig says, grimacing. “It’s good to see you, Ludig. I’m glad you’re safe and here to look after the crew.”

“Ach, it pains me how few remain to look after. Who made it out with you?”

“Ozbeg made it; he was with me every step of the way,” Padrig ticks the survivors off on his fingers. “Aled, as well, now a few scars richer. Harri and Hartig; they carried one another through. Donal’s a lucky bastard; the Delvers never even cut him. And Quill, the quiet one.3 Just half, all told.”

“Damn,” Ludig says. “Damn, damn. Dagmer, dead. Sonam and Sabi, too. Even Ionas. I’m sorry, Padrig.”

“No, I’m sorry. It was my job to get them out, right and tight. Couldn’t do it,” Padrig replies.

“Don’t chew your dagger over it, man. It was an impossible situation. And speaking of those — I’m glad you’ve returned. Things are unsettled around here. This job in Marshedge seems gut — easy, quiet work if we play it right — but Brennan is intent on stirring the pot,” Ludig says, his voice dropping to a whisper. “Recruiting new guardsmen, squeezing the townsfolk for coin. There’s nothing wrong with making sure the crew prospers, but he’s up to something. You were always the most reasonable of Brennan’s inner circle. Now that you’re back, you can talk some sense into him.”

Padrig shakes his head. “I’m not back, Ludig. Gordin’s Delve was my last go-round with Brennan. He’s done right by me; I’ve done right by him. I’m here to let him know that I’m hanging up my sword and finding somewhere to rest for a while.”

Ludig’s face falls. “Aurscheiße4. Say it isn’t true. Pad, we need you. I’m not the only one who thinks so,” he says. But when he sees the resolve on Padrig’s face, he nods sadly. “I understand. You’ve been with the Claws a long time. Buried many friends.”

“Aye,” Padrig says. “You know better than most that you can’t save everyone when we go into danger. But those that died, what did they die for? What do we have to show for it? I can’t stomach the waste anymore.”

The pair goes quiet as a handful of guardsmen pass by. Padrig recognizes one of them from the old days, flanked by a couple of fresh-faced recruits. Ludwig watches them pass and then whispers to Padrig. “Just be careful how you tell Brennan. He knows his hold on the crew is shaky, after what happened in the Delve.”

“If he rages and storms, I’ll weather it. He can’t hang me like he did Ulrikke — I’m not plotting against him, I just want to muster out,” Padrig says. “One last thing — Aled was asking after young Brogan, one of Ivan’s lads. Do you know what happened to him?”

Ludig looks downcast. “Ivan left him behind to hold the caravanserai door when we escaped through the tunnel. The rumor is that he was one of the few taken alive. If he still lives, no doubt he toils in chains in one of the more unpleasant Delves. Tell Aled I am sorry,” he says.

Padrig nods and takes Ludig’s hand again. “Take care of yourself, my friend. Thanks for all your wise counsel. And your steady hand with the needle, for all those stitches.”

“And you, Padrig. You can find Brennan in the Guard Hall, on the north side of the tower. Good luck,” he replies.

Scene 5: The Guard Hall

The central arched gate of the donjon opens up into a great circular yard, formed by the high, thick stone wall built by the Makers and surrounded by structures of timber, plaster, and thatch, clinging to the ancient slabs. The Guard Hall looms over the yard, two stories up, built into a ragged hole in the side of the tower. From the eaves hang the banners of the Old Families — a serpent, a heron, a carp, and a thistle — along with the willow of Marshedge. Padrig grimly notes a sixth banner as he ascends the stairs to the guard hall — a field of white emblazoned with a red, three-taloned claw.

The main room of the guard hall is a barracks — rows of bunked cots, enough to sleep 50 fighters in shifts, with a central mess area and galley. Padrig spots Maeve, the dark-haired gate sergeant, attended by a knot of guardsmen on the west side of the room. He marks them as veterans — well-worn leather gear, patched armor, an occasional dent in a half-helm.

Near the mess is another handful of guards — some are fresh, uncertain faces, but Padrig recognizes a few from Ivan’s crew. When they spot him, they once again point and whisper among themselves.5 Padrig nods as he passes and one of the old Claws puts her fist to her chest in a slow salute. He returns it before he opens the door to the Marshal’s study.

The study is well-appointed — a fireplace, chiseled from the stone slabs of the Maker’s tower, a large, polished white willow council table surrounded by high-backed seats, and a small bedroom, set aside from the rest of the study by lacquered wooden screens. The walls are adorned with sewn tapestries depicting the founders of Marshedge atop the Hill, attended by the first members of the Guard, and on the floor is the tanned hide of a massive crocodilian — 15 feet long at least, with six legs, tipped by curving black claws.

Brennan sits at the head of the table, Bertrim at his left hand, carefully going over a list of names. “This one is quite well-to-do but deeply disliked by his peers in the glassblower’s guild,” Bertrim says with a bland smile. “I’m sure if I sniff about his household, I can find a crime serious enough to confiscate his properties and apportion them to the Guard, and his guildmates might even thank us for it.”

But Brennan isn’t listening — he’s seen Padrig enter. A smile illuminates his handsome face, and he quickly rises to his feet. Brennan is of age with Padrig, but he has always looked more youthful — expressive and energetic, his emotions always playing across his face and in his aetherium-blue eyes. His blond hair is cut short, and the beard he had last time Padrig saw him has been shorn clean. He wears a dark green wool tunic, dyed with the white willow of Marshedge, atop polished steel scales, and at his hip hangs a longsword in a fine leather sheath, its hilt inlaid with silver.

“Padrig,” he says, opening his arms and approaching Pad for an embrace. “Bertrim told me you were here, but I couldn’t believe it until I saw you with my own eyes. Thank all the gods, it’s true. You’re alive.”

Padrig stops short of approaching him. “Aye. Alive, despite the Delvers’ best efforts. Many of mine weren’t so lucky,” he says.

There’s a momentary flash of annoyance on Brennan’s face before he goes somber, and he clasps his hands together. “Someday, we will have vengeance on Jahalim and his bootlickers for their betrayal,” he says. “I promise you; our friends will rest easy in their graves. Trust.”

“I’ve had enough of vengeance, Brennan,” Padrig says.

“Yes. Yes, of course, you’re right. Onward,” he says, nodding vigorously. “It’s hard for me to forget so many good warriors lost, but we have the living to think of. And Padrig, we are doing so well here. I don’t want to tempt the fates, but I think Marshedge is it — our republic of warriors. Your greener country, our new home.”

“Our republic? It seems like the Old Families have a firm grip on it,” Padrig says.

Brennan grins, a flash of mania in his eyes. “A grip, yes, but not firm. They’re not fighters — their forebearers had some grit to settle in such a terrible place, I’ll grant them that, but their descendants have grown fat, lolling around in luxury. They need help holding onto what they’ve got; that’s why they hired us in the first place,” Brennan explains. He sidles up to Padrig and puts an arm around his shoulder, leading him towards the council table. Bertrim watches the two with the same smile on his face. “So good to see you again, Padrig. I’m glad you found your way here,” he crows.

“And now that you have, we can begin in earnest,” Brennan says. “Things are turning to our advantage here, but we’re going to have to act boldly, soon. Ivan’s been recruiting more guardsmen who we can trust to follow our lead if we need to show some iron. Cousin Bertrim’s been up to his old tricks with the merchants and the guilds. We need you out in the fen — the Old Families have some secret dealings out there in the wilds, and if they move against us, we need to know what they are.” He pauses for a breath. “Who do you have left from the Delve?”

Padrig sighs. “A half-dozen of the scouts made it out. Oz, the twins, Aled, Donal, and Quill,” he says.

Frustration and anger flash on Brennan’s face but are quickly replaced by sympathy. “So few. Ionas, too. I know you two were close, Padrig. I’m sorry.”

“We’re all sorry. That’s why I’m done, Brennan,” Padrig says, almost blurting it out.

Brennan’s face freezes. He lets go of Padrig’s shoulder and turns to face him. “Come again?” he asks.

“I’m getting out. I’ve shed the same blood in the same mud as you for better than forty seasons. More than we ever thought we’d have. Getting out of the Delve was a close call. I don’t have any more close calls in me,” Padrig says.6

“Padrig, don’t you see? We’re all so close to getting out together,” Brennan says. “If we get set up here, in Marshedge, all that’s needed is to man the palisade and keep the braziers burning. No more Hillfolk feuds, no more Delver gangs, no more caravan masters barking orders. We’ll walk the streets, and folk will nod in respect. We’ll live in manor houses; we’ll go home at night to our wives and husbands, sons and daughters. And we’ll answer to no one but one another. The republic of warriors. Like we always dreamed about.”

“That was your dream, Brennan. I liked the tale well enough around the campfire, but by the time we got to Gordin’s Delve, I just wanted a quiet corner of the world to rest a bit,” Padrig says. “If it’s all the same to you, I want to go find it. I’ll send the rest of the crew on to you. Ozbeg can lead them well enough.”

Brennan turns from Padrig, going back to the council table and taking up a carved goblet and a stone pitcher. He pours a cup of wine as he holds forth. “You can’t leave now, Padrig. Not when we’re so close to our goal. Marshedge was a windfall — when we arrived, their old Marshal was dead, they were beset on all sides by bandits and creatures from the fen, and the Old Families couldn’t do anything but squabble. What else could this be than the hand of fate, clearing the path for us? The Delve wasn’t a disaster, it was a crucible. It prepared us for what was to come!” He takes up the cup and offers it to Padrig, who shakes his head.

“Maybe so. But it’s your fate, not mine,” Padrig says, his voice shaking just a bit.

Brennan’s jaw sets. His eyes search Padrig’s face. “I can’t do this without you, Padrig. When we thought you were dead, I despaired. I wept for you — you’re like a son to me, and I feared our republic might have died with you. If you leave, it’s not just your fate you’re denying. It’s all of ours. We’ve all fought so hard, sacrificed so much to get here. And you want just to throw it all away?” Brennan drains the goblet and slams it down on the willow table. “Where will you go?”

Padrig crosses his arms. “I haven’t decided yet. Wherever the wind blows me.”7

“Did you ever get back to Stonetop, Padrig? I recall you mentioning it long ago. And a merchant mentioned that he had come across a band of warrior companions who had taken up residence there,” Bertrim asks mildly. Brennan looks expectantly at Padrig.

“It was my home, once,” Padrig says, glaring at Bertrim. “I thought perhaps it might be again.”

Brennan nods thoughtfully. “Stonetop, eh? Yes. That might serve.” He turns to Bertrim. “How many fighters did your report say Stonetop could muster?”

“One hundred in arms, give or take. They are a militia, not an army, but they are strong, hardy folk, it is said,” Bertrim replies.

Brennan turns to Padrig. “Does that match your assessment?” Padrig doesn’t reply, but Brennan doesn’t wait. “Yes, you’re right, Padrig. Best you split off. It would be useful to have your eyes out in the fen, but we can recruit a few fen-walkers to our cause for such things,” he says, tapping his chin thoughtfully. “If you can put yourself at the head of a hundred screaming Stonetop savages, the Old Families could never move against us.”

Padrig shakes his head in disbelief. “Screaming savages? They’re farmers. And Brennan, what makes you think they’d even listen to me?”

Brennan breaks into sudden laughter. “This is why you need me, Padrig: You have no idea what you are capable of. I’d wager gold bezants ‘gainst copper that some folk in the militia are already whispering that you’d make a better leader than whatever stuffed fool they’ve got at their head now,” he says. He leans conspiratorially towards Padrig and mock-whispers, “And you can bet he’s heard them too, and is sharpening his blade for you even as we speak.”

Bertrim tents his fingers on the table and smiles. “Just imagine the story! A village of noble savages, at the edge of the world,” he says. “A prodigal son returned to lead them! A neighbor and ally in crisis. A friendship between warriors that brings peace to the land!”

Brennan turns to Padrig. “The hand of fate. Don’t tell me you can’t see it,” he says, his eyes burning, pleading.

“This fight just isn’t in me anymore, Brennan,” Padrig says.

Brennan sighs deeply and then nods. “I understand. I’ve felt the same way, more times than I can count. It’s not easy to keep going despite all we’ve lost, but we always do,” he says. He returns to Padrig and puts a hand on his shoulder. “Go back to Stonetop, with my blessing. Think about what I’ve said. I need you; the crew needs you. We’re so close to our dream being realized. You’ll see reason. I know it.”

Let’s pause this scene here. There are, of course, many things Padrig could say, but let’s break them down into two relatively sharp paths:

Be reasonable: Nod along with Brennan, and allow him to believe that Padrig is, or can be, won over. This is probably the more cautious path forward, but there are risks: If and when Brennan finds out Padrig is not on board, he might feel very betrayed indeed, and the folk of Stonetop might misunderstand things if Brennan’s plans for them came to light.

Be unreasonable: If Padrig gives an inch, Brennan will take a mile. Padrig draws the line here. What’s Brennan going to do, after all? Kill him?

We’ll decide the Marshal’s course with another reader’s poll — I’m excited to see whether this one is as clear-cut as the last! I was a bit torn as to whether or not to have Padrig trigger the Seek Insight move, trying to get some extra information about Brenan’s disposition, which might effect his choice. In the end, I decided to let the conversation speak for itself, but if y’all have any questions you want to ask (including but not limited to the questions from Seek Insight) that might inform your vote, feel free to throw them into the comments and I’ll answer ‘em.

Next episode, we’ll conclude this scene, and follow Anwen to the fen-walker’s guild hall in search of answers. Thanks, as always, for reading! (Voting closed as of 1/20/22)

Next Episode: Session 4.3: Betrayers

Vahid asking for more money is certainly something a player might do in this context, and as a GM, I’d probably let them run with it, even without an additional roll. The weak hit result introduces a new danger for Vahid, so it’s fair to be a little more generous.

Once the elemental energy is contained by the Azure Hand, it must be discharged — either as an attack, a vessel to contain it, harmlessly into the earth, or to power some other magic. Vahid is using that last ability to create the light show with the glowing Makerglass shards.

The Marshal’s crew has six members by default, and so far we’ve only given names to 5, so number six will be Quiet Quill.

“Aurochs shit” — Derrived from the Old Germanic word for aurochs, which were not yet extinct when those Iron Age tribes inhabited Europe.

Padrig uses Seek Insight here, scores a strong hit, and learns a bit more about the factions within the Guard — veterans, recruits and ex-Claws.

Padrig attempts to trigger Persaude here, but Brennan is not persuadable on this topic, so the move doesn’t trigger. This raises an interesting question: Padrig’s player is certainly aware that the move doesn’t trigger, but is Padrig aware that Brennan isn’t persuadable? For the purposes of this conversation, we’ll assume he is not aware of this fact — the characters are not aware that moves are triggering, I think.

Padrig triggers Defy Danger with Charisma here — he’s trying to stop Brennan from figuring out he’s based in Stonetop, at least for a little while. Sadly, he rolls a 5, and his +1 Charisma isn’t enough to squeak out a weak hit. Brennan knows exactly where he’s headed.

Brennan makes my skin crawl.

Based on having fought with him in the past as an Ally Padrig would know if he is the kind to take prisoners no?

Reason only goes so far when it comes to a man on a mission. I feel there is another option which doesn't sound like Padrig but more Vahids style and that is counter intelligence and manuvering. Building a faction all his own. Brennan gave away a bit too much when he said that he needs Padrig and that there are people whispering for him to lead. Which could very well be true.

Me thinks without Padrig his hold in the claws is no existent and we'd have Ivan or the like trying to take his head.

Judging by what’s happened before I vote unreasonable, although I view it more as him knowing that - as with children, albeit very dangerous ones - sometimes you just have to be harsh and deal with the fallout.

Also, loving this write up. Kudos!